New traffic controller discovered on the DNA railway

Traffic controller CFAP20. This illustration was generated using artificial intelligence.

&width=710&height=710)

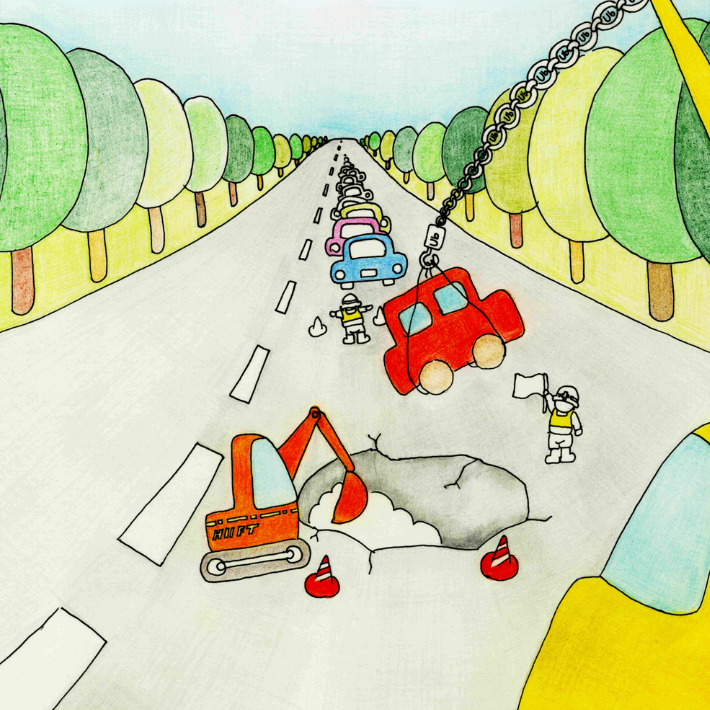

DNA can be seen as a busy railway track. Two types of trains race continuously along this track. One train copies the DNA (replication), allowing cells to divide. The other train reads the DNA (transcription) and produces mRNA, a shopping list that tells the cell what to do.

“The trains, called polymerases, move at one to two thousand bases per minute,” says researcher prof. dr. Martijn Luijsterburg. “Within a few minutes they can encounter each other. Especially at the start of a gene things often go wrong: the transcription train starts up slowly, while the copying train behind it is already picking up speed.”

Traffic controller preventing collisions

The protein called CFAP20 turns out to be the traffic controller that prevents this. It accelerates the transcription train so that it does not get hit from the rear. Without CFAP20, traffic jams occur. The transcription train stalls after starting and blocks the track. The copying train behind it cannot pass and crashes into it.

Luijsterburg: “Normally replication starts at thousands of sites simultaneously. Without CFAP20, half of them stop. The other half tries to compensate for the damage by speeding up. That sounds clever, but it actually creates new problems. It is like trying to copy a book in a hurry: lines get skipped. The result is a sloppy copy.”

Sloppy copies can lead to cancer

These sloppy copies cause gaps in the DNA and instability of the genome, the complete set of genes a human has. As a result, cells start dividing uncontrollably or following incorrect instructions. “Genome instability and stress during DNA copying and reading are well-known hallmarks of cancer,” says researcher Sidrit Uruci.

Uruci (on the left), Luijsterburg (on the right) and the other researchers involved in this Nature study did not discover CFAP20 itself: the existence of the protein was already known to scientists. “It was known as a protein in cell tails (cilia), but not in the cell nucleus. No one had ever looked there,” says Uruci.

Luijsterburg has an explanation for this. According to him, the discovery was only possible because two research fields, replication (Uruci) and transcription (Luijsterburg), came together. “You have the transcription people who study DNA reading, and the replication people who study DNA copying. But those two hardly speak to each other. We decided to bring them together. That is precisely how we could see how replication and transcription influence each other.”

Without fundamental research, no one ever gets better

They are the first scientists ever to discover the important function of CFAP20 as a traffic controller. This does not immediately produce a medicine, but according to Luijsterburg, discoveries like these, form the foundation for future treatments. “Without fundamental research, we will never discover things like this. And then you can never translate such insights to the clinic and to patients. That is why it is so important that at LUMC we do both: fundamental research and translation into practice,” he explains. This transition does take time. For example, in the early 1990s, BRCA1 was discovered, a breast cancer gene that actress Angelina Jolie publicly brought to attention. Decades of research later, there are now chemotherapies that specifically target this gene, and we are still not fully there.

Study opens a new world

The study of CFAP20 opens a new world for researchers. It gives cancer biologists an additional explanation for how genome instability arises and cells derail. For drug developers, it offers a new point of attack, because tumor cells appear to depend on CFAP20. “They exploit the protein to divide faster, even though it comes at the expense of DNA quality. In the future, this could be a weak spot to combat tumor cells,” says Uruci.

For fundamental researchers, the study is proof that it pays to keep searching for unknown genes and proteins. “The human genome consists of 20,000 genes, but 99% of studies always focus on the same 10%. So who knows what else we will discover in the future,” Uruci concludes.

This research was made possible through financial support from the ERC Consolidator Grant, the NWO Vici Grant and others.

&width=710&height=710)